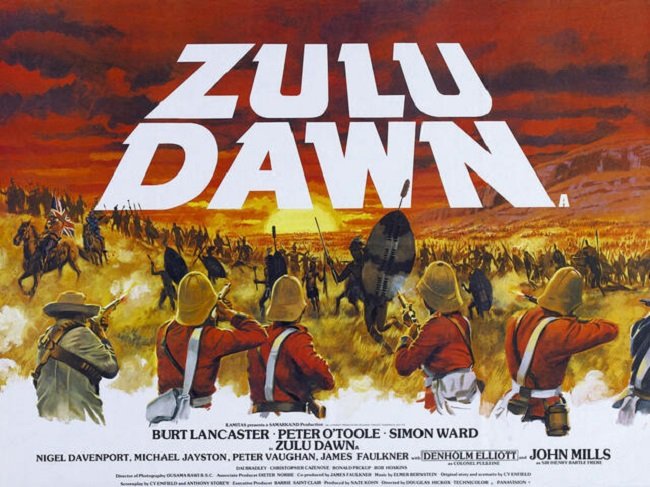

Zulu Dawn (1979)

Zulu (1964) recounts the Battle of Rorke’s Drift between the British Army and the Zulus in January 1879. Directed, produced and co-written by Cy Endfield the film presents an action filled account of how 150 British soldiers, 30 of whom were sick and wounded, successfully held off a force of 4,000 Zulu warriors. Although well made and rousing, it is very much a film from the British perspective. Despite depicting the Zulu nation fairly, the film makes no attempt to put the clash between two empires in any sort of wider context. Zulu Dawn is a direct prequel which shows the events that directly lead up to the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. Much more time is dedicated to exploring the Zulu’s position as their leader King Cetshwayo attempts to avoid the political fait accompli he has been presented with. Furthermore, Zulu Dawn does not in any way try to avoid the failure of the British chain of command that resulted in the defeat of 1,300 British soldiers at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Fearing that the Zulus are becoming too powerful in the region, Lord Chelmsford (Peter O'Toole) plots with diplomat Sir Henry Bartle Frere (John Mills) to annex the neighbouring Zulu Empire, despite there being an existing treaty in place. Subsequent demands to demilitarise are rejected by King Cetshwayo (Simon Sabela) giving Lord Chelmsford casus belli to invade. Prior to embarking into Zulu territory the British forces are reinforced with native troops and the Natal Mounted Police. However, the Zulus refuse to directly engage the British forces and pursue guerilla attacks. The British expeditionary force subsequently makes camp at Mount Isandlwana but rejects the advice from the Boer contingents to fortify the camp around the ammunition wagons. Lord Chelmsford divides his forces and heads a column to pursue bogus sightings of Zulu forces. Meanwhile the Zulu army masses near Isandlwana, preparing to engage the British camp.

Zulu Dawn takes time in setting the scene and explaining the historical situation. The first act cuts between a garden party being held by Sir Henry Bartle Frere, High Commissioner for Southern Africa and celebrations at Zulu capital, Ulundi. Both events provide a backdrop to ongoing political machinations. The screenplay by Cy Endfield cleverly uses the casual conversations between the officers wives and regional Missionaries to summarise the hubris and condescension of the British in Natal at the time. The disposition of the troops is also explored through the relationships between Colour Sergeant Williams (Bob Hoskins) and raw recruit Private Williams (Dai Bradley). Quartermaster Sergeant Bloomfield (Peter Vaughan) is shown to be a “jobsworth” and instrumental in contributing to the deteriorating situation at the film’s climax. Col. Durnford (Burt Lancaster) is shown to be savvy and well versed in fighting the Zulus. Hence his advice is scorned by his British superiors due to his Irish heritage.

The second act of Zulu Dawn follows the British as they make a series of ill conceived decisions after crossing into Zulu territory. Cinematographer Ousama Rawi makes effective use of the rugged South African terrain. The climax of the film follows in detail the attack upon the British lines by the Zulu and how they overwhelmed them. The subsequent retreat became a rout and one of the most serious defeats for British forces in their military history. Although not excessively explicit in its depiction of violence, director Douglas Hickox does well in depicting the growing sense of fear and disbelief among the British troops as they realise that the tide of the battle is rapidly turning against them. The failure to get ammunition from the wagons to the troops is a major factor. I suspect that the film’s depiction of a major defeat, rather than the usual narrative of the plucky underdog who wins despite the odds may discourage some viewers. Zulu Dawn is more likely to engage those seeking historical authenticity rather than pure action.