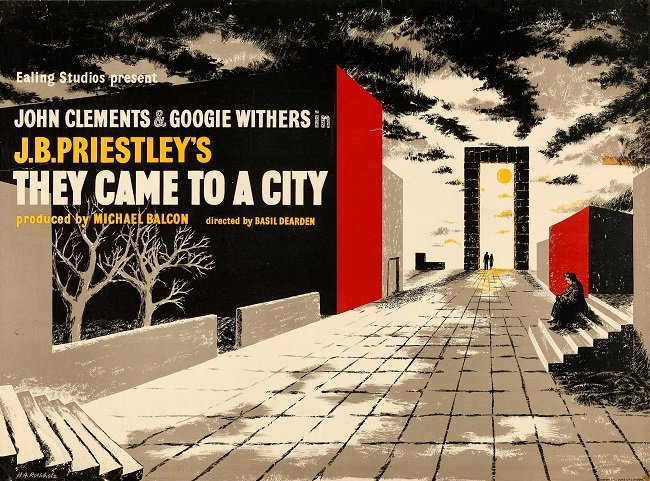

They Came to a City (1944)

Humanity struggling to survive a dystopian future has been a mainstay of pop culture for several hundred years. They Came to a City, made in 1944 as World War II was drawing to a close, takes the opposite approach in which nine individuals are shown a utopian future and given a choice whether to join it or return to their existing lives. This experimental film based on a play by J. B. Priestly, is dialogue driven and struggles with its transition to cinema. Yet the striking minimalist set design and art direction by Michael Relph, along with the crisp and beautifully framed black and white cinematography by Stanley Pavey make it visually compelling. Functionally directed by Ealing Studios stalwart, Basil Dearden, They Came to a City is not a lost classic but it certainly is an unusually cerebral and socially outspoken piece of wartime cinema.

Nine people from the different UK social classes, find themselves mysteriously transported to a modernist walled city. They include Sir George Gedney (A. E. Matthews), a misanthropic aristocrat; Malcolm Stritton (Raymond Huntley), a politically dissatisfied bank clerk and his neurotic and domineering wife Dorothy (Renee Gadd); Alice Foster (Googie Withers), an unhappy and exploited waitress; Mr. Cudworth (Norman Shelley), a money-obsessed banker; Lady Loxfield (Mabel Terry Lewis) a needy and class conscious widow and her put upon daughter Philippa (Frances Rowe); Joe Dinmore (John Clements) a world weary, free-thinking seaman; and Mrs. Batley (Ada Reeve), a practical and philosophical charwoman. An opulent door opens allowing them to visit the unseen city, which is hinted to be a social paradise. However, they subsequently have to choose whether to stay forever in the city or to leave and never return.

At first glance this is an excessively verbose story, told through the medium of British acting of the time, which can be quite jarring to the modern audience. However, the dialogue is clever, telling and socially honest with the wisest person being the ageing charwoman. Performances are strong and honest. The political and social philosophising may seem somewhat naive to casual viewers but this was very much the mood of the nation in 1944. The horrors of World War II drove a robust public debate for social change, which was succinctly demonstrated by Winston Churchill's defeat in the 1946 General Election. Playwright, novelist and social commentator J. B. Priestley was a wartime correspondent and felt that the status quo needed to be addressed in a postwar settlement. However, he was wise enough to realise that there would be strong resistance to such ideas and They Came to a City includes characters who dislike the notion of any sort of change.

Critics at the time, as well as contemporary analysis, often cite the notion of any utopia as flawed, as it runs counter to human nature. As seaman Joe Dinmore states “They’ll tell us we can’t change human nature. That’s the oldest excuse in the world for doing nothing”. There are further prescient observations about bankers and finance. When Mr. Cudworth recounts how he told a citizen of the city that he worked in banking, they replied “we call that crime”. Again naysayers point out the “school boy socialism” of Priestley’s dialogue but here we are 80 years later and the same sentiments about the exploitative nature of untrammelled capitalism are still being made. Overall They Came to a City is a cinematic curate's egg but an engaging one. It should be viewed with the national mood of the time in mind, as context is key to enjoying this social fantasy.