Falling Out Over Politics

“You cannot reason a person out of a position he did not reason himself into in the first place.” Jonathan Swift

For those who live outside of the UK, let me categorically state that Brexit has broken British politics. Prior to 2016, national politics still broadly functioned along traditional party political lines, with income and class substantially determining voter allegiance. The big three cities (London, Birmingham and Liverpool) maintained their liberal dispositions and Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales were dominated by their regional politics. Brexit changed all this creating fault lines that fell outside of the existing political status quo. Opinions differed based upon where you lived, how politically literate you were and even education. Your party political allegiance no longer indicated what stance you took on this matter. Furthermore, the discourse around this complex subject was quickly debased into a bipartisan culture war that was toxic and dangerous.

Seven years on, party politics are now fractured by factionalism and public discourse per se has taken on a more emotive and contentious tone. Brexit has divided not only politics but family and friends. The nature of the debate both in parliament and the national media has been far from convivial and has shown that many ideas and concepts that many thought were universally embraced, are in fact not. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown, the economic impact of the war in Ukraine and the rise of social media culture has further exacerbated political and societal divides. So I find it somewhat risible when I read such naive comments as “it’s amazing that people fall out over political opinions”, as I did on a national news website recently. The days of politely agreeing to disagree are long gone as UK politics becomes more like that of the US.

The generic nature of the two main UK political parties

To many observers outside of the UK, for decades our national politics has been a bland and somewhat predictable fight that took place in the centre ground. Extremes on both sides of the political divide have been confined to the wings. For anyone over a certain income, politics could be ignored because it did not appear to directly impact upon your life. It may well be a different matter for those on low incomes or marginalised minorities but as such groups did not have a substantive voice in political terms, the perception of a broad status quo that simply changed its custodian every 4 years, has endured. I have spoken many times to European friends who have struggled to discern any major political difference between the modern Conservative and Labour parties.

Hence during these times, if you differed with your friends, family or colleagues over fiscal policy, education or national infrastructure you could easily shrug it off. Even those invested in the distinct political ideology of a particular party tended to treat it more as an academic debate, rather than a religious credo. Obviously there would be some individuals who were diametrically opposed to others due to hardline political views but this was the exception and not the rule. Ultimately, any problems arising from political policy were the governments fault and not ours. All we have to do is turn up and vote every so many years and then complain during the intervening period. The Brexit referendum changed that due to its inherent nature and consequences. A referendum is a very direct form of politics which bypasses governmental policy and responsibility. The consequences therefore lie directly with the electorate, whether or not they understand and recognise this.

The realities of Brexit

As a result of the 2016 referendum the UK has left the European Union and there have been direct economic, sociopolitical and practical consequences, irrespective of one’s opinion of the rectitude of that decision. Businesses have subsequently closed, jobs have been lost and migrant employees have left the UK resulting in a labour shortage. The economy is stagnating and the cost of living is going up. Travelling to Europe has become more complex and costly. The consequences of Brexit are tangible and we all feel them. Hence it does not come as any surprise that friends, family and colleagues will come into conflict over this. Unlike a general election where the actions of the government can be blamed on its party membership that set policy, the ramifications of Brexit can be attributed to those who directly voted for it.

The UK is currently suffering from a stagnating economy, high inflation and labour shortages. Problems that have been exacerbated by nearly thirteen years of government by the same political party. Although the next election is not due until 2024, the Conservative Party are suffering greatly in the polls. The majority of the electorate attribute a lot of the aforementioned woes to their policies. However, due to the nature of the First Past the Post electoral system there is a chance that a targeted campaign of fear mongering and misinformation in the right marginal constituencies may well see them return to office. Despite having an electorate of 46.5 million, ultimately it is approximately 350,000 voters in swing seats that determine the outcome of UK General Elections. Such a clear disparity in the importance of an individual vote, makes the outcome of an election profoundly personal.

UK Doctors Demonstrating for increased pay

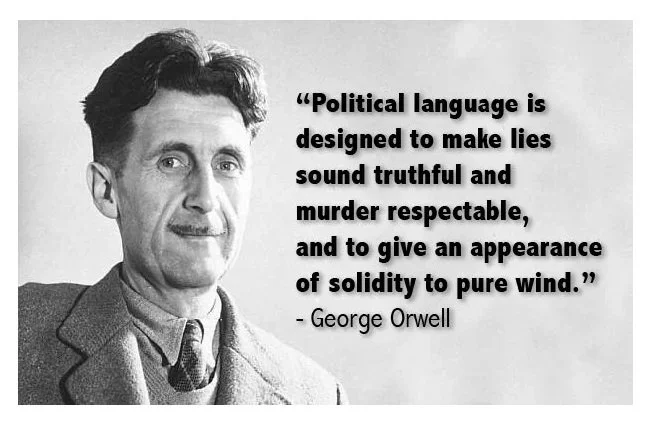

Some political journalists have suggested that politics may well “settle down” and return to being “remote” when the UK becomes economically stable once again. However, I think those days are gone, now that politics has embraced the culture wars and detached itself from facts, data, expertise and reasoned argument. The notion of doing what is collectively the best for all has been replaced with attacking and punishing groups that have been successfully “othered”. However, a growing part of the electorate have realised this, finding themselves on the wrong side of the dividing line. This shift in perception renders the voting habits of others highly personal. If your neighbour openly admits to voting for a party that subsequently limits your rights, taxes you further, or seeks to criminalise your actions then they are complicit in such outcomes.

I therefore suspect that falling out over politics is going to increase in the next decade. Politics in the UK is becoming more populist and less based in reality. Extreme policies are harmful to people and have real world consequences. Hence voting for such things is not something one can just shrug off. You will be judged by your actions. Such a sociopolitical climate will just further entrench tribalism. Your political views and affiliations will increasingly impact upon the decisions you make in life and shape your social circle, where you work and how you’re perceived by others. The notion of “I don’t date (insert political party here)” being part of your biography on a dating app, will no longer be some niche concept. It may even become a standard. If living in such a world worries you, then we need to make politics less partisan and return to agreeing to disagree. Sadly, I suspect that it is too late to put that particular genie back into the bottle.